The U.S. Navy plans to expand its submarine fleet at a cost of $200 billion, equivalent to the GDP of Ukraine. But as Republicans hotly debate ongoing military aid to Kiev, neither party has questioned the far more costly submarine program—allowing the Navy to conceal a startling fact about America's submarine fleet. The Navy calls its submarines "the most lethal and capable force." It is also the "silent service," shrouded in secrecy, the nature of its operations closely guarded.

The American attack submarine force—the "fighting" submarines—exists in order to pursue enemy submarines and ships, eavesdrop on adversaries and support operations by special forces. Hollywood productions like The Hunt for Red October have created the impression of submarines tracking the enemy while moving noiselessly under the sea, operating stealthily for months on end. The reality is markedly different. The U.S. Navy can deploy barely a quarter of its attack submarine force at any one time, and last year, despite a war raging in Ukraine and China's rise as a global superpower, only 10 percent of its submarines operated stealthily by spending more than 30 days fully submerged.

A three-month Newsweek investigation reveals the problematic arithmetic of contemporary submarine operations. Newsweek obtained classified documents that show the full scope of submarine activities in 2022; reviewed the work of submarine-spotters worldwide; and conducted extensive interviews with naval officers and experts. The conclusion is stark: American submarines never came out in what naval officers call a "surge" against Russia or China, nor did the overall force ever increase its level of operations.

"In some ways, this is just the cost of doing business," says one retired naval officer who spoke with Newsweek, explaining why the submarine force operates the way it does, and why it takes four submarines to deploy every one forward. "Could we be more transparent about what the boats actually do? And could we be so without harming the operational security of the force? Absolutely," says the officer, who requested anonymity because he is not authorized to speak publicly.

The Navy's $200 billion building program is aimed at increasing the number of its attack submarines from 50 to 66. That number is public. The statistic that's not discussed is that modern submarines have become so complex, the only way the Navy can appreciably increase its level of operations against Russia and China is by building many more. The Pentagon declares this an urgent task: China has the world's largest navy, and its submarine force is commonly described as catching up to the United States in quantity and quality. But as sluggish as the U.S. submarine performance is, Russia and China are even worse off. That raises further questions as to why the Navy is spending so much money in upgrading the attack submarine fleet, and in the ultimate value of such gold-plated machines.

Asked to respond to Newsweek's findings, Cmdr. Jackie Pau, U.S. Navy spokesperson, said: "Our undersea force is the most lethal and capable in the world, operating across the globe and ready to conduct prompt and persistent combat operations. We leverage our asymmetric advantages to deter war and, if deterrence fails, to dominate the adversary. Our Navy, including the submarine force, is ready to fight tonight to protect and support the American way of life."

Strike From the Deep

Over Memorial Day weekend last year, dignitaries, officers and sailors in dress uniform gathered on an exceptionally cloudy morning at Naval Submarine Base New London, Connecticut, for the commissioning of the USS Oregon (SSN 793), the Navy's first such in-person ceremony since the COVID pandemic.

The nuclear-powered USS Oregon, the Navy says, is 377 feet long, longer than the Statue of Liberty is tall. Equipped with the latest everything, it can fire long-range missiles and detect ships 3,000 miles away. With her crew of 132, 15 officers and 117 sailors, the submarine can dive below 800 feet and travel faster than 30 knots (35 miles per hour) while submerged. The Oregon is armed with 12 Tomahawk cruise missiles, some 40 torpedoes, can carry mines and anti-ship missiles and can employ drones and unmanned undersea vehicles.

"Soon Oregon will employ her stealth, her flexibility, her superior firepower and her endurance to travel silently throughout the world's oceans," said Adm. Frank Caldwell, director of the Navy's nuclear program, at the ceremony. Oregon will travel "undetected," he said, "preparing for battle and—if necessary—striking from the deep swiftly, without warning, to answer the nation's call."

Except not too soon. For nine months after joining the fleet, the Oregon was training its crew and testing its systems along the east coast. According to classified Navy records examined by Newsweek and the reports of submarine spotters, it left and returned to its Connecticut mooring on the Thames River 22 times for short training trips. Finally, on February 13 of this year, the USS Oregon left for its maiden European voyage with the Sixth Fleet, joining Dynamic Manta, a NATO anti-submarine warfare exercise held off Sicily in the Mediterranean Sea. During the second week of March, almost a year after being commissioned, the Oregon finally went stealth and into the ocean depths.

"Despite vastly greater capability and its pump-jet propulsion system, Oregon in some ways is no different than any other attack sub we have," says the retired Navy captain living in the San Diego area. The former skipper told Newsweek that routine maintenance and "work-ups" for future voyages constitute more than three-fourths of an American submarine's life. Over the planned 30-year life cycle of the Oregon, the submarine will go on 15 extended deployments, the Navy officially says. That comes to a cumulative 90 months, or indeed about 25 percent of the time.

"This should not be taken as a criticism of the Oregon," the retired Captain says. "This is how it's designed. Submarines are incredibly complex and when they do forward deploy, there is no question—especially when compared to other countries—how superior they are. But the task is difficult and many of the ideas about how many submarines we have out there and what they are doing comes from Hollywood."

"Can the United States surge more submarines in a war? Or operate more boats forward? Yes," says the captain, "but only for short periods of time."

Silent Isn't So Deadly

In 2022, the Navy commissioned two new submarines—the USS Oregon and the USS Montana—while retiring two 35-year-old boats. Fifty attack submarines formed the bulk of the overall nuclear-powered submarine force. The attack submarines are split between two fleets, with 24 in the Atlantic Fleet and 26 in the Pacific Fleet. The Atlantic submarines are homeported on the east coast, in Groton, Connecticut, or in Norfolk, Virginia. In the Pacific, attack submarines are deployed in San Diego, Washington state, and at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Five are homeported on the Micronesian island of Guam.

Regardless of the technical specs and the mythology, submarine operations are constrained by the laws of physics as well as by enemy activity. And despite the training and $10 billion-a-year infrastructure that backs them up, they are not perfect. For example, in October 2021, the USS Connecticut struck an undersea mountain in the South China Sea, injuring 11 sailors. The captain was relieved of duty after it limped into Guam. Though the Navy says the Connecticut suffered no major damage, the submarine did not leave its Bremerton, Washington, homeport in 2022.

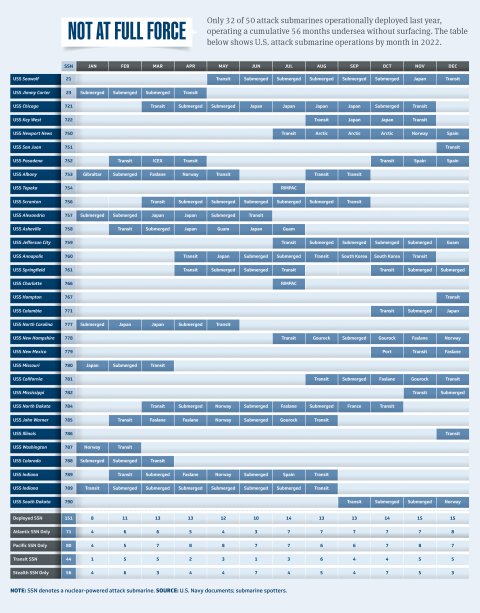

According to secret Navy records, only 32 of 50 attack submarines deployed in 2022. Those submarines spent a cumulative 151 months at sea, a quarter of what was theoretically possible. On average, 28 percent of their time at sea was in transit to and from Asia and Europe, making the actual time forward deployed and "on station" about 107 months. In other words, less than 20 percent of America's attack submarines were deployed and fully operational at any one time during a tumultuous year. It also means that the plan to increase the number of attack submarines from 50 to 66 effectively adds only four deployable forward subs.

"I thought they were out there all the time, you know, because the Russians are coming and the Chinese military is growing," says Hans Kristensen, the premier nuclear expert at the Federation of American Scientists, and someone who has studied submarines for decades, commenting on Newsweek's findings. "What these new numbers tell me is that the attack submarines are not war-winners."

The rationale for the Navy's submarine building plan is China. Xi Jinping's navy has a large diesel-powered fleet and is in the process of building more nuclear-powered boats that can operate beyond local waters. These submarines will increasingly threaten commercial shipping in the Indo-Pacific region as well as prey upon American warships, the U.S. Navy says. Russia has an attack submarine force of similar size, with about a third of them being nuclear powered. Even though the operational readiness of both navies is projected to remain far below their American counterparts, the U.S. Navy still concludes that it does not have enough to cover both theaters of war.

The fact is, even with an increase to 66 American attack submarines, only one quarter will continue to operate at any one time, still leaving a shortage. More numerous and cheaper non-nuclear submarines might seem to be an alternative, but such submarines would not be able to sustain the long-range deployments necessary for the U.S. to operate close to the Asian and European land masses. Meanwhile, the secrecy around the "silent service" keeps defense strategists from addressing the difference between technical superiority and actual usefulness. Superiority is not enough.

"Anti-submarine warfare in all of its dimensions is the answer...better detection, aircraft and surface ships, torpedoes and autonomous vehicles that can find and sink the enemy's submarines," says the retired Navy captain. "We can't afford, nor can we operate, only submarines to carry out the future tasks."

To fully appreciate the real-world operational constraints on attack submarines, consider the actual record from 2022. Navy records, including reports, individual logs and "contact" reports with enemy ships and submarines, show: The 32 deployed submarines spent almost 30 percent of their time in transit to and from waters near to Russia and China. When the deployed submarines were forward and "on station," they spent about a third of their time (37 percent) in "stealth" mode—that is, submerged and hidden. Against Russia, an average of six submarines were deployed at any one time in 2022, with only three submarines forward deployed in June. Against China, a slightly larger average of almost seven submarines were deployed at any one time in 2022, with as few as four deployed in January.

Stealth submarine patrols peaked in February, June and October, when six or seven total submarines operated fully submerged and hidden. Three submarines—the USS Seawolf, the USS Scranton and the USS Indiana—submerged for six months or more.

On average, fewer than five submarines across both fleets operated submerged and hidden in any one month. In March, the month after Russia invaded Ukraine, only three American attack submarines operated stealthily, two near Europe and one in the Pacific.

"Our submarines operate thousands of miles away from the American landmass," says a second retired Navy officer, currently a War College professor. "It's a balance...maintaining secure homeports in the United States and the long distances submarines have to travel to deploy to Europe and the Indo-Pacific. There is additional time, and wear and tear, because of the distances involved, but we are more than able to conduct our missions, and we are ever more mindful of being more dynamic in how we project the force."

Routine and Scheduled

Virtually all forward attack submarine operations take place in three places: near Asia—meaning largely the East and South China Seas; in the North Atlantic around the Norwegian and North Seas; and in the Mediterranean Sea. There is a range of missions: shadowing potential enemy ships, escorting vessels, showing the flag, joining exercises, intelligence gathering and special operations.

Two submarines ventured north of Alaska in March to break the ice some 170 nautical miles north of Prudhoe Bay, but it was more a routine annual exercise than a message of force to Russia. The Norfolk-based USS Albany had the year's most varied deployment—though while busier than most submarines, it also highlighted how little time was spent on forward missions. Albany started the year in Gibraltar, where it faced protests in the British territory from Spanish environmentalists.

After its five-day port call it headed for the Norwegian Sea. It was during the Albany's 73 days submerged that Russia invaded Ukraine to bring the biggest conflict to Europe since World War II. On March 20, the submarine pulled into the Faslane naval base in Scotland. It left after a few days and showed up in Tromsø, Norway, on April 5th. It operated stealthily for a couple more weeks in northern waters off Norway before arriving in its home port of Norfolk on May 14, having steamed 35,000 nautical miles.

On August 16, after routine maintenance and crew rotations, it left for the multinational UNITAS LXIII maritime exercise, sponsored by Brazil. The Albany moored at the Madeira submarine base in Itaguaí, Brazil, for five days in September before returning to Norfolk on September 26. Though the deployment to Brazil was never publicly acknowledged and the Navy is silent about what happened during its 73 stealth days in the Northern Atlantic, its voyages still had to fit with a planning schedule that can be arranged a year or more in advance.

"What you have to understand about submarine operations," says an active duty submarine squadron officer based in San Diego, "is that it's all about schedules. Subs can surge...sometimes even without notice...but even in a year like 2022 with all that was going on, it is very rare." The classified Navy documents bear that out. Only four submarines—the USS Mississippi, the USS New Mexico, the USS New Hampshire, the USS Connecticut—conducted "surge" deployments, that is, were ordered to leave outside of their planned sailing dates. According to secret Navy documents, none of the surges related to the top flashpoints Ukraine or Taiwan. They were merely practice. "The surges themselves are planned," shrugs the squadron officer.

Despite those rigid schedules, the war professor said the submarine force still does what the Navy calls "signaling:" Letting Russia and China know that the United States will assert itself as a global power, will support allies and will be present where enemy submarines operate. This is done by surfacing in unusual places or unexpected ways.

As an example, three Atlantic Fleet boats—the USS North Dakota, USS John Warner and the USS Indiana—made near simultaneous port calls in May in Russian neighbor Norway in an obvious signal to the Kremlin. The USS New Hampshire and USS South Dakota also showed up in Norway in December and then operated nearby with the USS New Mexico, which had surfaced in Scotland.

In the latest "Commanders Intent 4.0," issued by the submarine force chief late last year, the Navy says that the submarine force is available "in response to contingencies across the globe," Though naval experts universally told Newsweek that attack submarines can deny Russia and China's ability to operate away from their coastal waters, they rarely need to.

The classified Navy records show there was no increase in overall deployments in 2022—but part of the reason there was no need for an increase was that Russian and Chinese submarines venture out even less than U.S. ones. Though the Pentagon says Russia is returning to Cold War submarine operation levels, even plying the waters off of the U.S. East Coast with newer submarines, classified Navy data seen by Newsweek says that is not true. There was no time in 2022 when Russia had more than two ballistic missile submarines deployed to sea—and most of the time it only had one. Russia's attack submarine force, moreover, barely left Russian waters.

"They mostly hang out in the bastions," says Kristensen, referring to the close and protected waters of the Barents Sea, the Bering Sea in the Pacific and the Sea of Okhotsk. Russian ballistic missile submarines left nearby waters only nine times in 2022, according to Navy data. Attack and cruise missile submarines deployed outside the bastions only 11 times. In each case, a single U.S. attack submarine shadowed the Russian boats, according to the secret Navy "contact" reports.

China is no better, and Beijing's submarine operations were also minor in 2022, though more robust than Russia's. According to the secret Navy data, most months between eight and 11 Chinese submarines operated beyond local waters, including one ballistic missile submarine patrol. But these submarines rarely left the protected seas around the mainland, including China's 16 nuclear-powered submarines.

"We have to go to them," Kristensen says, referring to Russian and Chinese operations mostly in coastal waters. It just isn't that often.

A Costly Endeavor

The U.S. Navy is embarking on its most expensive program ever to replace and expand the aging submarine force and to bring in still more complex and quiet boats to avoid (and detect) Russian and Chinese submarines, which, the Navy says, are themselves growing quieter.

"We must maintain our tactical undersea advantage, with the posture and capability to respond with stealth and speed," Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro told the Naval Submarine League Annual Symposium last November, underlining the measures to upgrade the attack submarine fleet. "To maintain and strengthen maritime dominance, we have to be serious about fielding and maintaining the right capabilities to deter adversaries and when called upon—win wars."

In the next decade, the $200 billion that the Pentagon plans to spend on new submarines represents about 60 percent of its total shipbuilding budget. For comparison, the entire 2024 Department of Defense budget request is $842 billion.

Four classes of submarines are under construction or planned: additional Virginia-class attack submarines to replace the Los Angeles class, a new class of "Columbia" ballistic missile submarines to replace the existing Ohio-class boats starting in 2031, a new large payload submarine to replace the current four cruise missile submarines, and a "next generation" SSN(X) to augment (and eventually replace) the Virginia-class boats.

The Navy's current goal is not only to modernize the nuclear-armed ballistic missile boats but also to expand the fleet of attack and cruise missile submarines. The current target is 66. That means building three to four submarines annually—assuming Congress approves. But the Navy's shipbuilding record has been poor. Over the past decade, it managed to complete necessary overhaul and maintenance on schedule only 20 to 30 percent of the time.

"We're really struggling," Vice Adm. Bill Galinis, head of Naval Sea Systems Command said in September. Construction of new boats is also months behind schedule—to the point that the Government Accountability Office recently reported that the projected schedule provided by the Navy is "not reliable."

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the next-generation attack submarines are projected at $7.2 billion each. The new Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines are estimated to cost around $8.3 billion each for the dozen planned, while the first ship will cost around $15 billion, one of the costliest weapon systems ever. The large payload-guided missile submarines are budgeted at $8.8 billion.

The Navy talks of quieter submarines along with incorporating a "tsunami of technology": artificial intelligence, quantum computing, transparent intelligence and more. But the most important technology currently augmenting the submarine force is uncrewed systems, aerial, at sea and underwater. Just as for soldiers on land, drones are already changing the way submariners do things. In the future, some experts say, they will transform the nature of anti-submarine warfare.

There is no question that after 20 years of post-9/11 operations in the Middle East, the American focus is shifting to countering China. There, the Navy believes, American submarines will face off not only in protecting U.S. and allied ships at sea, but also in deterring or thwarting any Chinese attack on what Beijing sees as the breakaway province of Taiwan.

While the submarine expansion might force the Chinese to spend money on the same technology and deplete their resources, in the way that U.S. Cold War technology investments helped push the former Soviet Union to breaking point, the question of the actual utility of the submarines is in greater doubt.

"There is no question that when it comes to our submarines, platform to platform, our boats are unmatchable," says a former Pentagon procurement executive.

"I'd say it's time to reevaluate our priorities. Especially when the Ukraine war has taught us about the importance of a different kind of depth, the depth of our inventories, how voracious real war is for basic guns and ammunition," he says. "We can't be so enamored of our own myths to miss this reality."

LETHAL & CAPABLE

The U.S. Navy's submarine force in 2022 included 50 "fast" attack submarines; 14 nuclear-armed Trident-type ballistic missile submarines, part of the strategic nuclear deterrent; and four guided missile submarines.

The attack submarine force has three different classes of boats: 26 older Los Angeles-class attack submarines (two of which will be retired in 2023); three Seawolf-class super submarines that are exceptionally quiet, fast and specially equipped; and 21 Virginia class attack submarines like the USS Oregon, a number that will also increase by two in 2023.

The four guided missile boats, quasi-members of the fighting force because they forward deploy and hunt for enemy ships and submarines, are the oldest U.S. submarines: 42-year-old Ohio-class boats that have had nuclear weapons removed and are now armed with conventional cruise missiles (they are slated for retirement).

Submarines are said to always be in one of four states: in overhaul or repair in port; "underway"—short periods at sea for qualifications, testing or training; "deployment"—extended periods for forward operations ranging from two to eight months; and "on patrol"—a term properly used only for ballistic missile submarines.

Ballistic missile and cruise missile submarines ("boomers") have two crews that rotate to maximize their time at sea. Attack submarines have only one crew and though their deployments are longer, they are also less frequent, largely to accommodate the needs of the crew.

Correction 04/24/23, 5:24 p.m. ET: Corrects time Oregon spent in training and testing