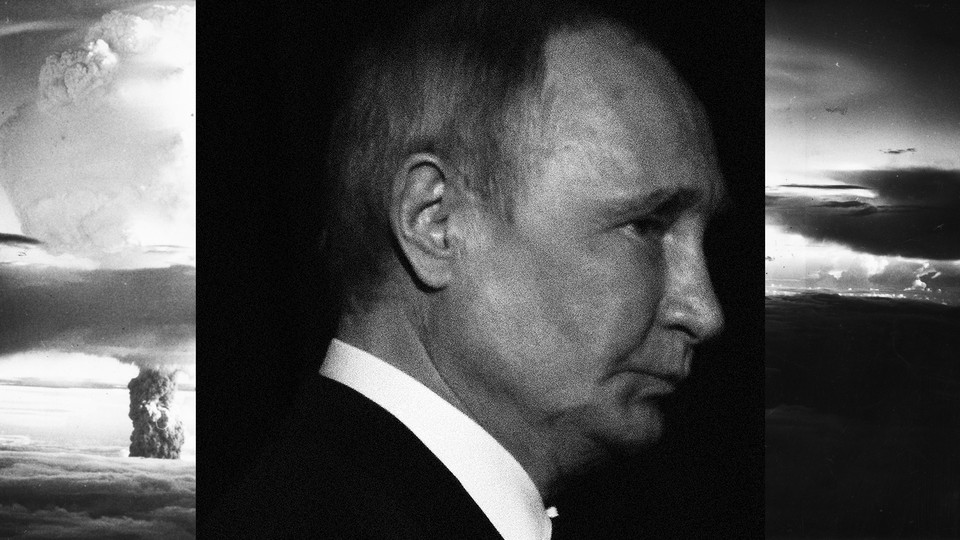

Putin’s Doomsday Scenario

The West cannot assume that the Russian leader will be a rational actor on nukes if he sees his nation and regime under existential threat.

When, in early October, President Joe Biden remarked that the risk of nuclear “Armageddon” was now at its highest since the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, he faced considerable skepticism and pushback. Yet senior U.S. officials appear to be taking the risk of an escalation involving nuclear weapons in Ukraine deadly seriously.

Later that month, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin jumped on the phone to his Russian counterpart, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, and spoke with him twice in three days after Shoigu had claimed that Ukrainian forces planned to use a nuclear “dirty bomb” and blame it on Moscow. The reasons for the Pentagon’s concern were clear: Russian falsehoods about a dirty bomb could pave the way for potential nuclear use by Russia.

American military leaders are worried that Moscow is embarking on a dangerous path of nuclear escalation amid the painful and humiliating setbacks that Russian forces have suffered on the battlefield in Ukraine. The latest reversal for Russia, and a significant indication of the trouble its military is having holding the territory it captured in the early weeks of its invasion, is the withdrawal from the city of Kherson, which weeks ago it had declared part of Russia.

What makes the situation so hazardous is President Vladimir Putin’s mercurial and impulsive decision making. From the start, the war in Ukraine has provided numerous examples of Putin’s emotional overreactions to events, and of his miscalculations. Putin’s move to annex Crimea in 2014 in response to revolution in Kyiv was one such decision, and it has given the peninsula a totemic significance in Russia’s war. Judging by his statements and conduct, the Russian leader appears to believe that the conflict he started has existential stakes for his country, his regime, and his rule, and that he can’t afford to lose.

Some people understandably prefer to believe that under no conditions would the Kremlin use nuclear weapons in Ukraine, and that Russian nuclear saber-rattling can be dismissed. This is, in my view, a false assurance, but let’s consider the arguments.

Eight months of war in Ukraine have provided plenty of examples of Moscow signaling red lines, then not following through on them. Back in March, Moscow issued a threat that it would target Western arms convoys entering Ukraine from NATO countries, to very little effect. In September, it declared that it would use all the means at its disposal to defend the four recently annexed Ukrainian regions. (When, days later, Ukrainian forces liberated the city of Lyman in one of those regions, Donetsk, Russia did not escalate matters.)

Others point to the Russian doctrine published in June 2020 that allows for the use of nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear power only if the very existence of the Russian state is at risk. This vague definition, they argue, means that the Kremlin might use nukes if “Russia proper” is attacked but that Putin would not use them to defend territories that, in international law, are part of Ukraine—including Crimea.

Then there is the notion that Putin might be deterred from going nuclear by the negative reaction Russia could face from its remaining economic partners—most notably, China, India, and Turkey. In addition, some analysts argue, the battleground efficacy of resorting to nuclear arms in Ukraine is questionable. Ukrainian forces have good mobility, which means that an attack on them with a tactical weapon, such as nuclear artillery, would require firing a lot of rounds that would have a dubious effect, and might also endanger Russian forces and the civilian population in Crimea and recently annexed territories.

So far, also, Ukrainian leaders and the general population have downplayed the psychological impact that the use of nuclear weapons could have. Finally, there is the hope that American deterrence and messaging will influence the Kremlin’s calculus. If the U.S., as some retired American four-star generals have suggested, threatens to use overwhelming conventional force against Russian military assets in Ukraine—including in Crimea—as a response to any nuclear attack, then Putin will back down.

So much for the case discounting any resort to nuclear weapons by Moscow. But given what we know about the Russian leader, no evidence suggests that he is prepared to vacate the illegally annexed territories—especially Crimea, which Putin sees as a defining aspect of his legacy. If Putin is unable to defend Crimea conventionally, then not to use all means at his disposal, including nuclear weapons, could lead to his being perceived in Moscow as weak; in Putin’s eyes at least, that could endanger his domestic political survival. The Kremlin’s equivocal messaging about its red lines, and its failure to enforce them, doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

Neither should anyone set too much store by the ostensible restrictions in Russian nuclear doctrine. Despite them, as many senior Russian officials have pointed out, the doctrine allows for the use of nuclear weapons to defend Russian territory against conventional aggression. Furthermore, their vague language could give Putin plenty of room for maneuver—something seen in the serial instances on his watch in which Russian laws, including the constitution itself, have been bent or violated.

From Moscow’s point of view, the illegally annexed territories now belong to Russia. Accordingly, losing them to an invading army would mean one thing: Russia’s nuclear arsenal is no deterrent to any potential aggressor. The way that senior Ukrainian officials have been framing the breakup of Russia as a desired outcome of the war is not helpful—serving only to confirm Putin in his long-held belief that the West’s goal in supporting Ukraine is regime change in Moscow and the destruction of his country.

As for the reaction of Russia’s major partners like China, the Kremlin knows full well that Beijing will not use its economic leverage to deter Russia. Xi Jinping might warn against nuclear war, but he won’t threaten the Kremlin with breaking economic and military relations should Moscow use nuclear weapons in Ukraine. Beijing knows it is unlikely to reap any reward from the U.S. for putting pressure on the Kremlin to fix a problem that China sees as American-made. India and Turkey have so far voiced concern about possible nuclear escalation in Ukraine only in vague terms, and have also refrained from suggesting that they might impose any real consequences should Russia indeed use weapons of mass destruction.

The Kremlin believes that the devastation inflicted by the Russian air bombardment of Ukrainian infrastructure will be a rude awakening for President Volodymyr Zelensky and the Ukrainian people, and make them more clear-eyed about Putin’s determination to fight by all means possible—including nuclear weapons, should that remain the only option for him to not lose this war. Russian leadership also still labors under the misperception that Ukraine’s leaders have no agency, and that Zelensky and his team are beholden to the U.S. If the White House wishes, the thinking goes, Ukrainian military advances can be stopped and Kyiv can be brought to the negotiating table.

Finally, Russian leadership believes that no American president will risk a nuclear war with Russia over a non-NATO member, even Ukraine. The Kremlin believes that Biden understands this when he says that Putin “is not joking.” The Russians believe that any U.S. military response to a Russian nuclear escalation would most likely be conventional, such as U.S. strikes to destroy the Russian Black Sea fleet or other targets within Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders. But the Kremlin also believes that Washington may be inhibited even in this response, on the assumption that such actions would lead to further Russian escalation. Putin probably judges that U.S. nuclear deterrence in this context means a nuclear response only as a last resort.

Putin also takes inspiration from his experience dealing with the U.S. in 2013, when President Barack Obama declared the use of chemical weapons a red line yet failed to act when the Syrian tyrant Bashar al-Assad crossed it. The White House preferred to reach a deal with the Kremlin rather than use military force. The calculation in Moscow is that something similar will happen this time around.

None of this provides any assurance that Putin will continue to exercise nuclear restraint. The bad news is that the military situation could deteriorate very quickly for the Kremlin, and then Putin, caught off guard by a series of setbacks from the front lines, might act impulsively. Worse, if a nuclear crisis should arise, the chances of successful diplomacy are slim. Putin does not seem to have abandoned his maximalist ambitions of subjugating Ukraine, and is likely to use any cease-fire the Kremlin would agree to as an opportunity to rebuild the Russian military machine and return to combat.

For his part, Zelensky is attuned to the dominant sentiment among Ukrainians, who are ready to fight to the bitter end after seeing the war crimes in Bucha and elsewhere. Ukraine’s war goals call for a return to the 1991 borders, including Crimea. That’s where Moscow’s and Kyiv’s red lines clash, with no chance now of reconciling them.

The good news is that, for now, the Western intelligence community has noted no changes in Russia’s nuclear posture. Putin appears convinced that the tools he is already using in Ukraine will ultimately work.

The mobilization that Moscow conducted in response to the Ukrainian counteroffensive in September has helped stabilize the front lines for the time being. The targeting of Ukrainian infrastructure that followed the explosion on the Crimea bridge a month ago is slowly but surely knocking out power stations and water supply across Ukraine, including in major population centers such as Kyiv and Kharkiv. This trend, the Kremlin hopes, will not only undermine the Ukrainian military advance but also force millions of civilians to abandon their homes in winter and seek refuge in other European countries, increasing the migration pressure on Ukraine’s allies.

Finally, Russia’s energy war on Europe has not yet been as successful as the Kremlin had hoped, because of a relatively warm fall and the European Union’s ability to fill gas storage. But Moscow knows that the coming winter will be more difficult for Europeans, when they will have to compete with the rest of the world for expensive liquified natural gas, given stopped Russian pipelines. Putin hopes that the combination of these factors will gradually erode Western support for Ukraine, and make it unnecessary for him to resort to the nuclear option.

That is obviously not the West’s desired outcome, so the U.S. needs to prepare for what Putin might do if this strategy stalls or fails. Addressing a nuclear escalation will require the U.S. to have a functioning communication channel with Russia. Although, as National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan recently revealed, these channels are not entirely moribund, no diplomatic progress on the nuclear issue has been visible.

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, American and European leaders likened communication with their Kremlin counterparts to talking to a TV set tuned to a Russian propaganda station. And Moscow is still speaking from that script.